In the spring of 1950, I was suffering from repeated stomach pains and was admitted into the South London Children’s Hospital, in Lower Sydenham, where I had an appendix operation. The resulting scar was quite long and appeared to be 2 separate incisions (like somebody missed the first time), and it took 11 metal clips and 3 stitches to seal. I was there for 3 weeks.

At that time, I was going through puberty and felt strange most days. Sometimes I would find myself talking or being talked to, and I would seem to be out of my body and seeing everything from a great distance, like in a dream. I wish that somebody could have explained what was happening, as it was quite frightening. It was much like being very ‘stoned’.

That May I joined the youth club at Christ Church in Beckenham, where I played my first games of table-tennis, and had a great fondness for the sport ever since.

In early August I was obliged to move back with the family at 60 Blenheim Road, Penge, as my grandfather Herbert Henry Jeffery, who I shared a bedroom with, became seriously Ill, and would die a few weeks later.

By now I was going regularly to the Crystal Palace grounds, either fishing in the early mornings, of spending whole days there exploring with brother John. We never had food with us, and would experiment by eating various leaves and plants, nibbling acorns, and the Hawthorne berries and leaves. We’d catch beautiful butterflies and moths, and everywhere was overgrown and full of wild flowers and shrubs, and play around the Prehistoric Monsters there.

In the summer holidays I walked with friends to the Keston Ponds, near the famous World War II, Biggin Hill Airfield, where we fished for sticklebacks, and having learned the way there, I would walk there with my brother John and spend days there and on Hayes Common. It took us forever to walk there and back, and I discovered years later that the distance there from home was over 10 miles each way. Looking back now, those distances seem enormous for young children, but in those days it was the only way to get anywhere, without money for public transport.

I returned to school in September, still having problems with dad at home, and I had lost interest in the choir and piano lessons. I would play all the classical pieces I’d learned, in the wrong rhythms and speeds, making my parents very angry, but amused my brothers and sisters. I wanted to be fishing or playing sport in the street or the local parks.

I would visit my dad’s family in Sydenham regularly, and play records on their wind-up record player, as I was by now becoming more aware of music.

At school in January 1951 I ran in the 5 mile Cross Country race on Hayes Common, feeling proud by coming 52nd out of about 250 boys.

Starting in June, my friend and I took on the weekend job of scoring for the Lloyds Bank cricket team at Beckenham. Travelling to away games by coach and relishing the lunches and afternoon teas. I became an obsessive follower of the game, continuing to visit my grandmother’s house to watch the Test matches on her tiny TV with her.

That month, we finally had electricity installed in the family home, and dad had the Relay Radio installed. It was a small speaker with a volume control and a 4 positional switch that allowed us to hear the three BBC services – the Home Service, the Light Programme, and the Third Service, and also bad reception from Radio Luxembourg.

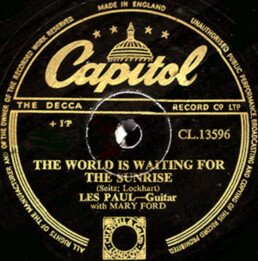

It was a revelation to us children, and we became fascinated with the comedy programs, and the popular detective series ‘Dick Barton – Special Agent’. However, the popular music in England at that time was incredibly bland and offered nothing for young people. But suddenly a great sound caught my ear: ‘How High the Moon’ by Les Paul and Mary Ford, and Les Paul became the first person to turn me on to the guitar sound, and I was fortunate years later to have him as a friend.

January 1952 brought another low in the Perks household. The appallingly bad weather meant father was out of work for weeks. He ran out of his savings, and asked to borrow the money in my post office savings book which gran had saved for me throughout the war. It equalled about two weeks’ wages for dad. And he took me to the post office, where I was made to draw it out and give it to him. A few of years later, I asked when he was going to repay me, and he struck me, and accusing me of being ‘ungrateful’. He never paid me back.

On Saturday 2nd February 1952, King George VI died in his sleep at Sandringham, aged 56.

That June, I went to the Lord’s cricket ground in London for the first time and watch the third day’s play of the England versus India Test Match, where England’s great wicket keeper Godfrey Evans scored a century. A few days later I returned and saw India’s Vinoo Mankad score 184.

Towards the end of term, we did mock-exams for the O-Levels, which we would take in a year’s time. I did well in Maths, Art, Music and Geography, but failed miserably in all other subjects, especially Algebra and Trigonometry.

That summer I watched a lot of the Olympics on Gran Jeffery’s TV, and I remember the great Czech runner Emil Zatopek, who won 3 Gold Medals, and the Engliand’s Harry Llewellyn, who rode ‘Fox Hunter’ to our only Gold Medal.

In December, a great smog fell on London for 5 days. We’d had fogs before, but you could taste this one, and once again, when we blew our noses, the handkerchiefs were black. Visibility was literally down to a few feet and everyone got lost, even to walk to the shops around the corner. The walks to school and back were major expeditions.

In February 1953, sweet rationing finally ended, and there were crazy scenes in the shops, which were stripped bare, and took weeks to settle down again.

A month later I saw singer Johnny Ray on the London Palladium on gran’s TV, where he was mobbed onstage by girls, and had his trousers torn and shredded, and I became a fan.

After my on-going problems with dad, relationships disintegrated even more at home. My parents seemed resentful of everything I did, and we argued continually. I had to share a bed with my two brothers, and even now at the age of sixteen I had to be home by ten o’clock every night: Father was a disciplinarian.

Together with all of these pressures at home, a thunderbolt was unleashed on me by my father. He wrote to my headmaster, ‘Jumbo’ White, saying that I would be leaving school at Easter just two months before I was to sit the GCE examinations — the major reason for being at such a fine school. Father said he was pulling me out of school because he’d found me a job working for a London bookmaker. He was convinced that there was a big future for me there, and with me learning the trade, he could then open his own betting company. I was dumbfounded to say the least, but had no say in the matter.

My headmaster, Mr.L.W.White, replied to father’s letter, asking him to change his mind and keep me at school until I had completed my Exams, but father, who was a stubborn man, wouldn’t change his mind. I kept that letter because it marked an important moment in my life.

So, on the first Monday after Easter, I nervously left home and travelled by train to Victoria Station, then on to Bond Street Station by the tube. I found the City Tote offices, over an opticians at 71 Duke Street, London. Business was conducted purely by phone, and I began work as a Junior Clerk, starting at £3.10.0d per week.

A few weeks later my job entailed me to take films of telephoned betting slips to the Bank tube station, to be developed near St Paul’s, and I was shocked to see that everywhere around the cathedral was still completely destroyed down to the basements by the bombing in the war. The reconstruction of the City was only just beginning.

On 17th May 1953, the last of the Ration Books were issued.

My wages went nowhere, as I was forced to give mother £2.10.0d, which left me less than a pound a week to travel to work, have a meat roll and tea for lunch, leaving nothing for clothes and entertainment. At that time you could buy cigarettes, 5 or 10 to the packet, and if you couldn’t afford that, they would sell you individual ones.

However, we were all uplifted in spirits, when on Wednesday 6th May 1953, our own Roger Bannister broke the 4-milute mile barrier for the first time, and just three weeks later on 29th May, Edmund Hillary and Sherpa ‘Tiger’ Tensing Norkay became the first climbers to conquer Mount Everest, for Britain. But these great moments were soon topped on 2nd June, when our Princess Elizabeth was crowned Queen of England at Westminster Abbey.

By now, I had made friends with Albert Stone, a fireman’s son who lived near me, and I made up a foursome with him and 2 local girls. My girl’s father had been at Dunkirk in the war and talked to me about his experiences, and her brother played me my first jazz records: Dizzy Gillespie, Gerry Mulligan and a band called Kenny Graham and his Afro-Cubists.

Because of this, I badly wanted my own record-player and records, but money was scarce, and so I took my stamp collection that my grandma Jeffery had helped me assemble during the war to a second-hand shop and sold it for £3 10s – the best price I could get. It was worth considerably more, but I needed the money. I went on to a record shop in Anerley and bought an old wind-up record player and a box of needles for £2 10s, and my first 78rpm records: Les Paul and Mary Ford’s ‘The World is Waiting for the Sunrise’, and Johnny Ray’s ‘Glad Rag Doll, that reminded me of my girlfriend at the time.

Early the following year, I became interested in a new radio show that has since become legendary – ‘The Goons’ featured Peter Sellers, Spike Milligan and Harry Secombe. With my usual concentration to detail, I can remember many of the zany jokes and episodes well, and I loved the great, timeless humour. I was fortunate in later years to get to know Sellers and Seacombe, and become a close friend of Spike Milligan.

As October 1954 arrived, and my eighteenth birthday neared, I joined many of my mates in fear of the arrival of the dreaded call-up papers for the compulsory two years’ National Service in the Army, RAF or Navy.

I was still listening to the weekly Goons Shows on radio, but started to hear a newer comedy show featuring Tony Hancock called ‘Hancock’s Half Hour’ which became very popular, and Hancock ended up as one of mine, and one of Charlie Watts’ favourite English comedians of all time.

One of the first records Bill purchased – Les Paul and Mary Ford’s ‘The World is Waiting for the Sunrise’.

On Thursday 20th January 1955 I reported at RAF Cardington in Cambridgeshire, and ceased to have a name – just a number and rank: 2745787 Air Craftsman 2 Perks, W.G. My pay was 28 shillings per week (£1.40p in today’s money). We were kitted out and shown the basic routines, and I was posted to RAF Padgate, near Warrington, Lancashire. This was reputed to be the hardest camp of them all, and proved to be the case.

On arrival there, we were billeted in huts of 20 boys. We each had a metal bed, an upright cupboard, and a small bedside cupboard. In the centre of the hut was a metal stove. This winter was very cold, and so were we, and we were allowed to use the stove for heating, but were rationed to one bucket of coal a day.

We were not allowed to leave the Camp during our 8 weeks here, and were subjected to daily drills, parades, physical training and inspections. Anything that didn’t meet with the approval of the NCO’s, was punished with guard duties and cookhouse fatigues. We were warned that if we didn’t pass out after 8 weeks, we would have to stay here for another term, and heard that one recruit had become so depressed, that he hung himself in our hut a few weeks before we arrived.

In February, we did rifle and Bren gun training, lying in the snow in just underclothes under boiler suits, and boots. It was so cold that I contracted frostbite on my left hand, and was treated at the medical section for some time. We had to take cold showers, and were supervised to make sure we did. We did live grenade training, and were subjected to tear gas, where we were led into a room and exposed to it until our eyes streamed.

On Monday 21st March I passed out of basic training here, and was given a week’s leave at home before being posted to Hereford for trade training. This camp, RAF Credenhill, was a nice relaxed camp and much more bearable. Once settled in, we would go into town chat to the friendly local girls, and sample the scrumpy (cider), which was very potent, and then stagger back to camp, well soused. We had a radio speaker fitted in our hut, and were able to listen to the popular music of the day on BFN (British Forces Network). At the time the hits were Tennessee Ernie Ford’s ‘Rain’ and Perez Prado’s ‘Cherry Pink’, and songs by Eartha Kitt and the Crewcuts.

I left RAF Credenhill on 9th July 1955 as a qualified Clerk Progress. I returned home and joined the family again before I was posted to West Germany a few days later. On Monday 18th July I left home with my kit-bag over my shoulder and travelled to London where I caught the train to Harwich with many other army personnel headed for Germany. At Harwich, I was surprised to go through customs, before boarding a flat-bottomed troop ship and ushered down into the bowels. There we settled into three-tiered bunks and set sail for the Hook of Holland overnight. This was my first ever trip out of England. It was hot and stuffy, but it was a smooth passage and I slept most of the 7 hours it took to cross the Channel.

We docked at 7am and continued the journey by train. I heard that I was posted to RAF Oldenburg, 2nd TAF (Tactical Air Force Wing), BAOR 25 (British Army of the Rhine), and arrived there late the next afternoon.

On Thursday 21st July, I went to the MT (motor transport) Section, of the Technical Wing, where I would be working, and was shown to my desk. I was sharing an office with a Corporal Ryan and two German civilians called Walter Hanke and Rudi. Walter was very serious and efficient, while Rudi was a comic and often played jokes. My job was dealing with fuel and repairs both on the camp and on the airfield, and I also kept detailed accounting of all vehicles on the camp.

I made a few excursions into town to look around the shops, stopping for wonderful cheap snacks in the streets of tasty Bockwurste and Bratwurste sausages and delicious bowls of what was called mock-turtle soup. In September I joined the MT Section football team, and became mates with a boy named Gordon Lee Whyman, a fabulous player in the style of the great Rodney Marsh.

We clubbed together and bought a radio for our room, and were able to listen to AFN (American Forces Network) Radio. We would wake up at 5.30am to country music on a programme called ‘The Stick Buddy Jamboree’, and also heard the beginnings of rock ‘n’ roll, by Elvis Presley, Bill Haley, Fats Domino, and Little Richard.

I was promoted to LAC (Leading Air Craftsman) and returned home for 10 days leave. I managed to wangle a lift in an RAF truck and cross to Dover. We caught the train to London, which luckily passed through Penge East Station, just a mile from home. I jumped off the train onto the tracks and the boys threw my kit-bag down. The train moved off, and I was arrested by the station officials, who wanted to charge me, but luckily they let me go. I walked home happily and surprised the family, but when father saw me all he said was “Hello Bill, home again? – when do you go back?”

I discovered that mum had thrown away all my personal items, including my diaries and scrapbooks I made throughout my childhood in the war, and my school papers and reports. I was shocked, but I didn’t fully recognise the importance of this disaster until years later.

When leave ended I sailed back to the Hook of Holland in very rough weather. All on board were seasick during the 7-hour journey. We weren’t allowed on deck, and sat it out below, trying to find a toilet or sink that was vacant. I’d never been so miserable in my life.

In the NAAFI, we drank tea that was laced with Bromide, supposedly to reduce our sex drives. So, instead of going into town, we ended up in the German dancehall and bar nearby called Zum Grunen Wald, where local girls hung out with us. The jukebox featured all the latest rock ‘n’ roll records from America, which was wonderful.

On 20th June 1956 we bought tickets to see the Stan Kenton band perform in Bremen. During our walk around town we discovered the US Military PSI Shop, and ended up buying a few of the new Rock ‘n’ Roll 45 singles of Elvis and other artists. Later we saw a great concert by the Kenton Band, with Mel Lewis on drums and Bill Perkins on sax. We loved the ‘Peanut Vendor’ and ‘Artistry In Rhythm’, where the band played those great discords.

In July I returned home on leave, and went shopping and bought one of the first fleck jackets, which were all the rage. By now impressing girls was high on my list and I decided to contact a girl I’d been writing to from camp. She was a nurse called Anne Worsall, and lived near West Wickham, five miles from home, and we met at her house. She was blonde and extremely pretty, and had one eye slightly off-centre, which made her very attractive.

I returned to Oldenburg that August, and was, by this time, completely obsessed with rock ‘n’ roll music, and I went straight into town and bought myself a Spanish acoustic guitar for 400 marks (about £30 at the time), and fooled around with it. But I found it almost impossible to play, owing to the height of the strings on the fret-board that cut my fingers. I ended up tuning it to a chord – making things a lot easier, but prohibiting me from learning to play chords.

One night in October the girl from the Grunen Wald that I liked invited me home with her. She said she lived with her grandmother, and we took a late train to her village, just outside of town, and went to her house. In the early morning we heard a bump on the floor upstairs, and she was really scared, and said it was her dad, getting ready for work, and I had to quickly leave. I rushed into my clothes, said goodbye, jumped out of the window, and walked to the station. I waited for the train together with other commuters, knowing that her dad was one of them. I returned to the camp happy, but never did it again.

During that year of 1956 there had been a few serious accidents with the Hunter jets. One plane had crashed on landing, and the wing tore through a chequered caravan and a truck on the side of the runway, decapitating 3 airmen inside. Then we heard about a pilot that got his hand caught high up in the cockpit while flying upside down, and had acid from the batteries dripping on him. He ended up landing the plane with one hand. I felt happy not being a pilot.

January 1957 arrived, and I started to take driving lessons on three-and-a-half ton Magerus trucks, learning to double de-clutch, changing gears. I became a ‘B’ driver and over the ensuing months I went on a number of day and night convoys, driving in the snow and ice on the cobbled streets. I would then occasionally drive in convoys to other British RAF camps like Bielefeldt. These experiences put me in good stead for driving years later.

After the extremely cold January and February months, the weather had improved by March, and I played football again with the MT Section team where I got to know Gordon Lee Whyman a lot better. He always looked really funky, and made quite an impression on me. Years later I would legally change my name to a version of his. We stayed friends until he passed away a few years ago.

When I was on leave again in June I called Anne Worsell, but she was going steady. She introduced me to a very attractive nurse at Swanley Hospital, Kent, so we went to the cinema and on to a cafe for a bite to eat. When we got back to the hospital I realised my last train had gone, and I was 13 miles from home. I went to the local police station and they gave me a cup of tea and flagged down a lorry on the bypass that took me to Lewisham. I walked home from there, which took me a few hours, and I got to bed exhausted. A few nights later, the same thing happened, and I went back to the police station. They said ‘not you again’, but got me another lift. Yet another long walk, but felt it was well worth it.

Back at Oldenburg I met a guitar player on camp called Casey Jones, and we formed a little skiffle band together briefly. I made myself a tea-chest bass with a broom handle and string that cut my hands every time I played it. Years later Casey Jones had a group in Liverpool called Casey Jones And The Engineers, and had some minor success, and Eric Clapton told me years later that he played with them briefly in October 1963, before joining the Yardbirds.

On Monday 21st October 1957, I returned home on leave to celebrate my 21st birthday, but heard that dad’s brother Frederic Perks had died from Asian Flu the day before. I ended up having a very subdued 21st birthday at home 3 days later.

In early January 1958, I flew back to England to be demobbed, and after a few days of formalities, I returned home a civilian, to live with my family at 60 Blenheim Road, Penge.

A major event in my life came in February 1958 when I went to the Regal Cinema in Beckenham with friends and saw the film ‘Rock Rock Rock’. All was normal, until the Johnny Burnett Trio performed ‘Lonesome Train’, and then Chuck Berry appeared in a white suit singing ‘You Can’t Catch Me’. And as he started doing his leg movements, the whole audience started laughing, thinking it was a comedy number. My hair stood up on the back of my neck and I got cold shivers. I’ve never been affected by that feeling before or since, and I became a dedicated Chuck Berry fan from that moment.

His records were not available in England, and I would have to order them directly from America. Singles would take a month to arrive, and I waited 3 months for his album ‘One Dozen Berries’. I also ordered singles by other artists at the time, and suddenly, it seemed, rock ‘n’ roll music was everywhere. Jerry Lee Lewis’s ‘Great Balls of Fire’ went to Number One in England, to be replaced by Elvis Presley’s ‘Jailhouse Rock’.

That February, I decided to get a job, and I went for interviews at insurance companies, Otis Elevators, and other office vacancies, but as soon as they heard that my last job was working for a bookmaker, I heard no more – Thanks dad.

A few weeks later I finally managed to get employment working in the offices of W.Weddell and Company, meat importers, in the Royal Victoria Docks, East Ham for £6 10s. per week. I travelled there by train and bus but owing to my low wages, I decided to complete the 13-mile journey there and back by bicycle, which saved me a pound a week. It involved me walking through the Greenwich Tunnel with my bicycle, to get to the north side of the River Thames.

By now I had reunited with my friend Albert Stone, who had finish his National Service in the army, and we would hang out in the popular coffee bar in Beckenham High Street. Since the advent of skiffle, coffee bars had become all the rage throughout England. We also went to the Beckenham Ballroom, as in those days that was pretty much the best way to meet girls. We also went to the Royston Ballroom in Penge, run by the famous dance team, Frank and Peggy Spencer.

One night we were sitting having coffee on the balcony there, and a friend pointed out some girls he knew, and I said how much I liked one of them. We invited them up for coffee and I chatted to her. Her name was Diane Maureen Cory, she was seventeen and lived with her widower father and younger sister in Kirkdale Road, Upper Sydenham. She had very black, curly hair and a cheerful personality, and had a little Spanish blood, through a grandparent. She worked at Barclays Bank in Millbank, London, preparing customer’s bank statements.

We started to go out together and I discovered that she was into sports, having been long-jump champion at school, played netball, and followed the Crystal Palace football team like me. We went with friends went to dances and spent most evenings at the Three Tuns Hotel in Beckenham High Street. We began to visit her relatives in Dulwich, Beckenham and Bromley, and her cousins in Park Langley, where I first heard the music of one of my greatest idols – Fats Waller.

On Monday 26th May 1958, Diane and I went to see Jerry Lee Lewis perform at the Granada, Tooting. It was the third concert of the tour and he was magnificent, He returned to America, where his great new single ‘High School Confidential’ was banned by almost all radio stations and his career nose-dived, before he justifiably re-surfaced years later to become a country music legend.

A few months later Diane and I went to see Lonnie Donegan in concert, and he was so great, that I jumped out of my seat, together with other boys, and danced in the aisles for the first and only time in my life.

By September, I had become tired of cycling backwards and forwards to the Royal Victoria Docks, and left W.Weddell and Co, and got a better job at John A.Sparks, the Diesel Engineers at Streatham Hill, London, as storekeeper and progress clerk for £11 per week, and I would leave home at 6am and travel there from Penge by train.

Diane and I started to go to the Crystal Palace football matches at Selhurst Park, Norwood, and would travel there on the 654 Trolley Bus (Run on electric cables) from Anerley Hill. That month we saw them in a 4th Division match, where our idol Johnny Byrne was playing, and they had their biggest win ever, beating Barrow 9-0. Byrne would later play for England.

On Thursday 29th January 1959, Britain suffered the worst winter fog since 1952, which crippled transport throughout the country, and made it impossible for us to go anywhere.

A week later my uncle Jack Jeffery gave me his old Brownie box camera, and I started taking occasional photos around Penge and Beckenham, when I could afford it.

In March, after rows with her father, my girlfriend Diane moved in with us at Blenheim Road. We were now watching the Crystal Palace football team regularly and go with friends to The Three Tuns Hotel in Beckenham High Street, where we would socialise with drinks and play darts most evenings.

My workmate Jack Oliver, who was an amateur photographer, took photos of me at work, and visited his house at Crystal Palace a few times, and he showed me how he developed and printed photos in his dark room.

One day in May, Diane and I went to the dance at the Beckenham Ballroom, where I was refused entry because of my tight trousers, which were banned at the time. The next week we returned there, and I was wearing a fairly wide pair of trousers. They let me in, and safely inside I went into the toilets and took them off, revealing the tight pair underneath. People on the dance floor couldn’t understand how I got in. However, these strict regulations turned us off going there, and we continued to go to the Royston Ballroom, where we started to win the jiving competitions most weeks – our prize being free tickets for next week’s dance.

A little later we started to go to the Beckenham Baths to watch the Wrestling, and we saw the likes of Jackie Pallo, Steve McManus, The Royle Brothers, and the great Scottish world lightweight champion George Kidd, who was my favourite. He had learned the science of leverages, and successfully incorporated it into his fights. He held the world title for many years, with no real competition at his weight, and always fought men much heavier than himself, and always won.

On my 23rd birthday on Saturday 24th October 1959, I married Diane Maureen Cory at St John’s Church, Penge, with Albert Stone as my best man. After being together for eighteen months, we virtually drifted into marriage, following the custom of so many of our friends. We had a small wedding reception at the King Alfred Pub, in Southend Lane, Bellingham, London.

We moved into a house in Woodbine Grove, Penge and lodged with a Mr.Chapman. An inauspicious start to a doomed marriage, finding from the start that we were not compatible, and the marriage began failing before it really got started – but we persevered.

We had no money to go on honeymoon, and so the following week, when England’s first motorway, the M1, opened. Diane and I decided to visit my old RAF friend Jim Bottrell in Smethwick, Birmingham, for the weekend. Half-way up the M1 I realized that we had left his new address at home. Since we only had enough petrol money for the one trip, I decided to continue and chance my luck. Diane thought I was crazy and kept insisting we should return home, and we argued throughout the drive. However I drove on to Birmingham.

When we arrived in the outskirts, I used every bit of logic I could muster, and followed the signs to Smethwick. Then the challenge really began, and I drove to the centre of town – and remembering the house had a number in the hundreds – I looked for a long road. At a traffic light, I chose the first one we saw, turned left, and drove half-way up that road on the brow of the rise. I stopped, not knowing what more to do. I saw an old woman sweeping her steps across the road, and I walked over and asked her if she knew my friend, who’d just moved in a week ago. She said that two doors down a couple had moved in that week with a new baby. I walked down and knocked on the door and Jim Bottrell opened it, proving that miracles really do happen.