In January 1940, as Ration Books were issued to the general public, it continued to snow and freeze, and the River Thames froze for the first time since 1888, and the worst storms of the century swept England.

That April I accidentally swallowed a torch bulb, and mother took me to the South London Children’s Hospital around the corner. The doctor made me eat a sandwich of bread and cotton wool. I can never explain the awful feeling of biting into it and having to swallow it. I’ve had a revulsion of touching cotton wool ever since.

The Battle of Britain began on 8th August 1940 when massive raids of over 1,000 German planes were being sent over daily. I was nearly four years old, and I remember standing in the street with mum and dad and neighbours, seeing the sky full of formations of German bombers with a heavy continuous drone. Amongst them were the white trails of our fighter planes, and everyone was cheering. The blitz of London continued, and we were obliged to spend most nights sleeping in our air raid shelters.

After a quiet Christmas, that I have no memory of, Germany continued with massive bombing raids that caused fires to rage out of control throughout London. And when Germany looked like they were winning, the weather changed for the worst, and the raids eased. But in March the bombing recommenced, and we spent most nights and often days in the shelters. Then in May, London was subjected to a final onslaught of almost 600 planes that rained bombs and incendiaries on London, and the loss of life was at its worst.

In June my father, being a builder, had to travel the 130 miles north to Nottingham to build and repair hangars on the airfields there, and a month later mother and us three children travelled to Nottingham to join him. He befriended a kind family called Crowder in Mansfield Woodhouse, and they agreed to give us temporary accommodation. They lived in Sherwood Street, and soon made us feel at home.

After the summer holidays, I started to attend York Street School, a good mile away. To get there I walked past farms and the coal tips at the Sherwood Colliery, where buckets of coal waste travel along the high wires to form new tips. When I saw the Michael Caine film ‘Get Carter’ in 1971, shot in Newcastle, it featured almost identical scenes.

In December the Japanese Air Force attacked Pearl Harbour, destroying most of the American Pacific fleet, Britain and America declared war on Japan and my father was enlisted into the army.

Back at school I was being hit by the lady teacher, for refusing to speak in the local dialect, and I unhappily played truant with other boys. My mother found out, and arranged for me to return to London to live with her mother.

So in August 1942, not yet 6, mother took me to Nottingham and put me on the train to London, and I travelled alone. On arrival, my grandmother Jeffery met me and we went on to her home – the upstairs flat at 36 Blenheim Road. There I moved in with my gran Jeffery, granddad, a lodger, and my aunt Dorothy, who worked at The Admiralty in London. We had gas lighting, no heating or bathroom, & as usual, the toilet was in the garden, with the Air Raid Shelter.

I had no toys, and grandma gave me a little china house to play with, and just before sleep, she would tell me stories and rhymes. She was very affectionate to me, and I loved her dearly. A little later she began teaching me more things in preparation for school.

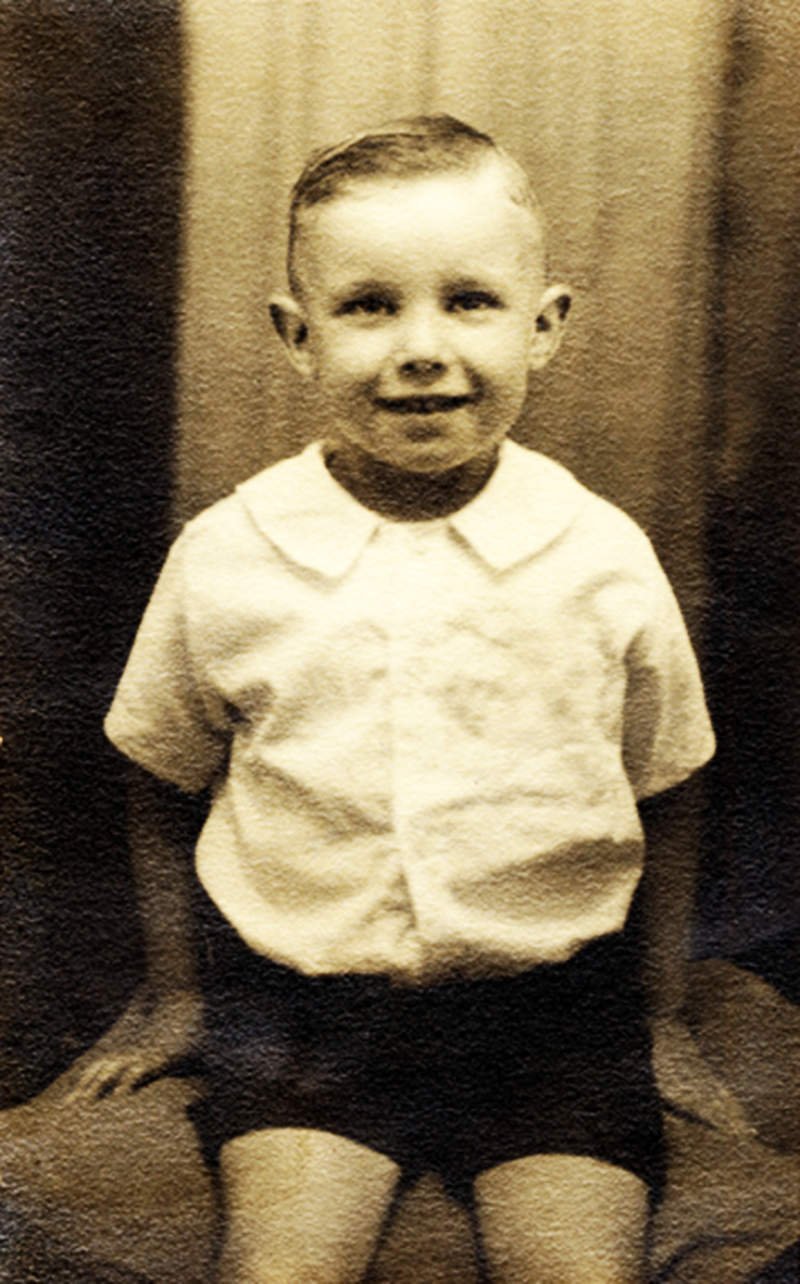

On 1st September 1942, grandma took me to a studio, where I had my photo taken. It was sent next day to my mother in Mansfield for her 25th birthday, and was dedicated to her by me on the back – ‘To dear mummy from Billy’. This is the earliest photo of me in existence, and my earliest writing.

A week later gran walked me to Melvin Infants School, where I continued my education and was far happier. There I was given a gas mask in a leather box with a shoulder strap. It was obligatory at the time to take it everywhere I went. By now the bombing had been reduced to just the occasional air raid.

The Number One record in the USA that winter was Bing Crosby’s ‘White Christmas’, from the film ‘Holiday Inn’, which became one of the biggest-selling single records of all time, and gran would sometimes sing it to me at bedtime.

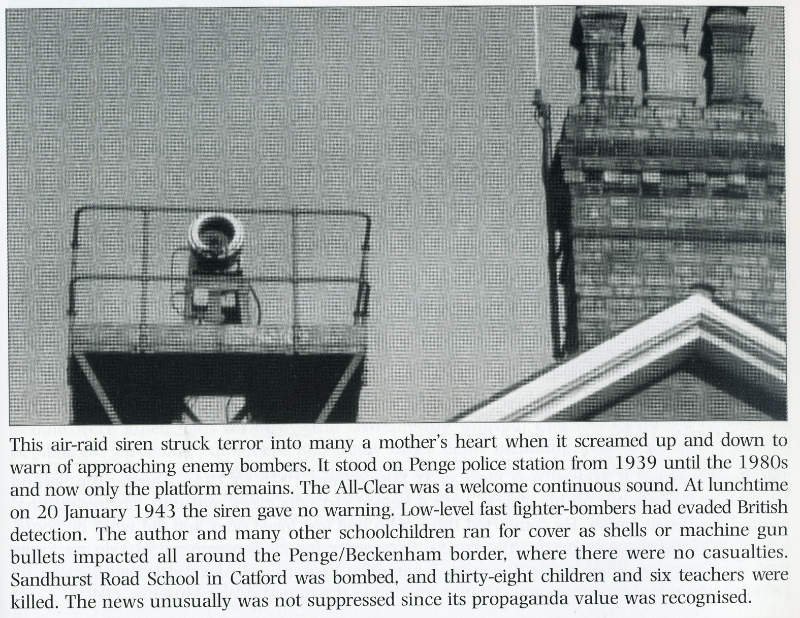

Leaving school at lunch-times, we’d go to the back of the pub nearby, and look through the fence at monkeys playing in a cage on the wall. While watching on Wednesday 20th January 1943, the air raid sirens went off, and we ran to our homes. When I arrived at the top of our street, I saw a German fighter-bomber roaring towards me just above the roof-tops, firing its guns. I ran and ducked behind the first coping-wall, as it passed overhead. Then I ran down to our flat, where gran hurried me down the back staircase, but stopped half-way as the plane returned, and we saw it roar past over the gardens through the large skylight window. We then got safely to the shelter.

After the all-clear sounded, we returned to the flat, and later that day we heard that this was one of the planes that had dropped a bomb on the Sandhurst School in Catford just three miles away, and machine-gunned the playground area, as children were rushing for safety. The strike killed 38 children aged between five and seven, and six staff. Our plane was unloading the last of its ammunition.

By early February, the bombing had eased, and mum and the kids returned from Mansfield, and moved in with dad’s family in Miall Road, Lower Sydenham, where I re-joined them.

A few weeks later, dad’s sisters, Dolly and Bessie, took me on the tram – a wonderfully noisy contraption with wooden seats – from Lower Sydenham to Honor Oak Park, where I took my very first few piano lessons from an old Austrian lady called Miss Oppenheimer.

In the following days I ran errands to local shops for the neighbours and earned pennies, and relatives would give me odd coins. I dreamed of having the little two-wheel bicycle in the shop down the road, and would give the shopkeeper my coins, which he entered in a book. My aunts and uncles were back and forth in their uniforms and also gave me odd coins.

In early April I took a few more coins down to the bicycle shop, where to my astonishment, the shopkeeper said that over the last four months I’d saved enough money, and the bicycle was now mine. I proudly pushed the 2-wheeler home, not knowing how to ride it, and on arrival, my mother accused me of stealing it, and promptly smacked me, insisting we return it. We went back, and the shop-keeper explained the whole thing to my astonished mother, and I dried my tears and kept my bike.

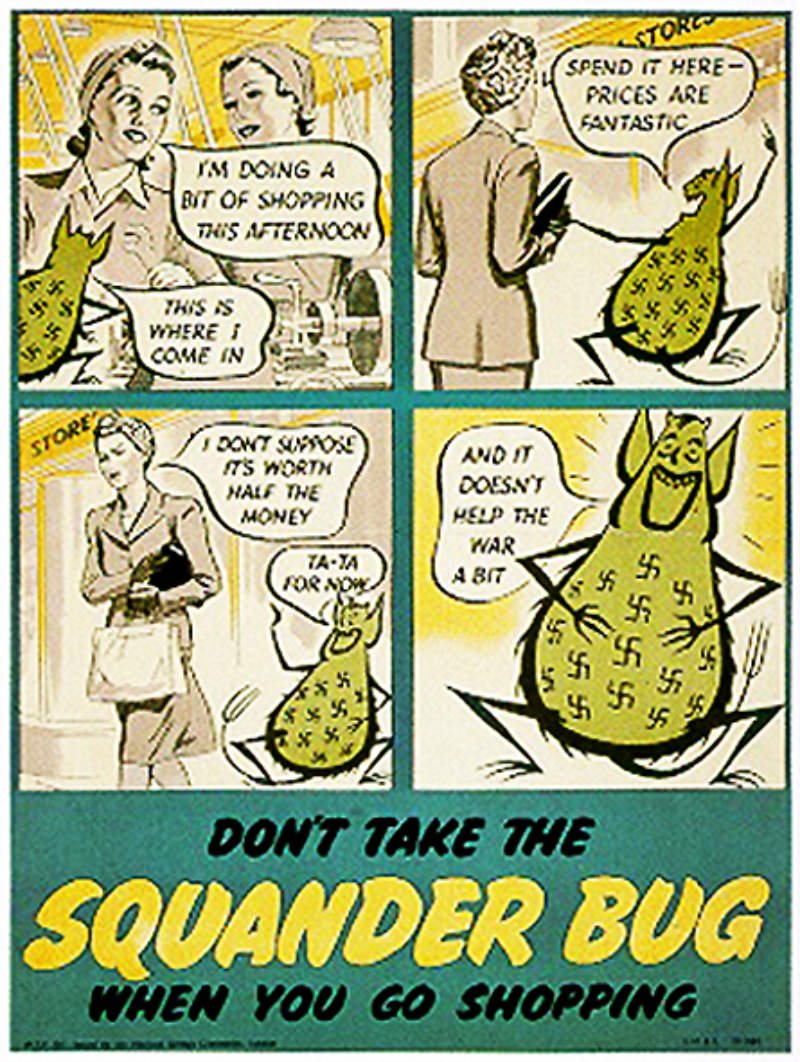

A few weeks later we moved into a flat at 32 Mosslea Road, near Penge East Station, and three families shared the house and air-raid shelter. From there I took the long walk to school with my gas mask, where we were taught air-raid drills, and safety precautions, and were shown propaganda films and war posters.

January 1944 arrived, and I began junior school at Oakfield Road School, Penge – nearer to where we lived. The classes were huge, with over forty pupils in each. At the school clinic we were given malt and orange juice, and treated for ringworm and scabies, which was horrific. Then dentistry, where teeth were pulled and drilled without anaesthetic – because of wartime. All of us children suffered from nits and fleas, and were constantly bitten by bed-bugs.

On 6th June, later called ‘D-Day’, the invasion of Europe took place by the allied troops of Britain and America, who stormed ashore in Normandy, which was great news. But then the V1 rocket attacks (Doodle-Bugs) on London commenced, and during one of these air-raids, our neighbour Mr Wheeler, took me out of the shelter and showed me one flying a good distance away, with flames spurting from its rear, and that droning sound we dreaded.

Then on 24th June 1944, the sirens sounded and we rushed to our shelter. The mothers had sandwiches and drinks prepared, not knowing how long we would be imprisoned. There we sat listening to the menacing drones of the doodle-bugs as they flew over, and then one got louder and louder, and suddenly stopped. The mothers threw themselves over us, and there was a few seconds of silence, and then a tremendous explosion shook the ground, and dust, dirt, leaves, and small branches were blown violently into the shelter and we were all coughing in the polluted air.

When the all clear sounded we emerged into a very different garden, with damage and debris everywhere. Looking back, we saw the backs of all of the houses damaged, with the huge French windows lying in the gardens. The flying bomb had glided over us to a street, and flattened a dozen houses. Upon entering our flat, we found every stitch of furniture flung against the walls nearest to the explosion, which seemed extremely odd.

Dad was given ‘enemy action leave’, and arranged for mother and the kids to return to the safety of Mansfield, while I returned to grandma Jeffery. Then a few days later another flying bomb fell around the corner in Laurel Grove, making a direct hit on an air raid shelter, and two girls in our class at school were killed.

To get my mind elsewhere, grandma bought me a small scrapbook, and I began to stick in things from newspapers and magazines, and wrote small diary entries. She also showed me her cigarette cards and stamps collections – which she later passed on to me. This began my desire to keep diaries and collect things.

We were still on heavy rationing, and managing on tins of dried milk, dried eggs, and dried potatoes. Our standard meat was rabbit, spam, and corned beef. Chicken or duck was a rare treat. There was no fruit.

In September 1944 Paris and Brussels were liberated, but we were still suffering from the odd doodle-bug, and now the V2 Rockets began to fall on England. Fortunately we had only one land in our vicinity, and that was near the Crystal Palace grounds, which was at the time used by the military.

In recent years I found a booklet on the Crystal Palace, Penge and Anerley areas, which had a diagram showing the bombs that fell in that one-mile radius of our home. It showed the one V2 rocket I just mentioned, sixteen V1 rockets (doodle-bugs), and 38 incendiary bombs. It was no wonder we spent half of the time living in the shelters during those harrowing years, listening to the dreaded wail of the air-raid sirens, the drone of German planes, and the sound of the anti-aircraft guns firing from the streets and the park nearby.

By now the bombing had eased off, and my aunt Dorothy, now 19-years-old, was going out with American and Canadian servicemen, who would give me chewing gum and chocolate. They took her to dances in Purley and Croydon, and she took me once, and I sat watching everyone dancing the jitterbug to the music of a great dance band, and from that day on I wanted to be in a band when I grew up, but I never really believed it would ever happen.

Grandma secured a house up the road for us, and mum and the kids returned from Mansfield and moved in, and I re-joined them. Living was as usual with gas lighting, no heating or bathroom, and the toilet in the garden. The house was always cold, and we shared a tooth-brush and salt, and washed in the kitchen sink. Food rationing was still in full force, and once we had to eat dandelion leaves between bread, as there was nothing else.

That November we had one of the few family photos taken, and a few days later, the American bandleader Glen Miller went missing while crossing the English Channel by plane in bad weather. He was just 40-years-old.

It was a very hard winter, and our bedroom was so cold that the ice would form on the inside of the window in beautiful patterns, and it was a nightmare getting out of bed onto that icy-cold linoleum floor and putting on freezing cold clothes, and going down to the kitchen to warm ourselves up beside the stove, before the walk to school.

On 28th April, Italian Dictator Benito Mussolini was captured by partisans near Lake Como and executed, and two days later Adolph Hitler committed suicide in his bunker in Berlin. Finally on Tuesday 8th May 1945, World War II ended in Europe, and was named ‘VE-Day’.

We had fabulous celebrations with flags and buntings from the windows of every house, and a wonderful street party with tables all the way down the centre of the street, and an enormous bonfire was lit in the middle of our road – celebrating peace at last.

After the war, Pamela Clarke’s father, who lived in Blenheim Road, bought a second-hand coach, and ran trips to Margate and Bognor Regis for kids in the street, and the older pensioners. He would years later successfully build the massive ‘Clarkes Coaches’ business.

In August 1945, the Americans dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Russia absurdly declared war on Japan, whose Emperor signed the unconditional surrender to the Allies, and we celebrated ‘VJ Day’ with another great street party and a bonfire.

That Christmas us kids enjoyed a shared gift of our first Rupert Annual, and this became our usual Christmas present from then on, and in recent years I’ve built up a complete set of Rupert Annuals from the very first one, printed in 1936 – the year of my birth, to the present day.

That year we had our usual wonderful Christmas party with dad’s relatives, with dad playing the piano, while grandfather entertained us by singing all the old music hall songs – which began my fondness for the Music Hall.

I started to go to Saturday morning cinema, at the Odeon, Penge, and would be mesmerised by the serials of cowboys, and my favourite – Flash Gordon.

On Saturday 8th June, all of us school children received a proclamation Letter, for VJ Day, from King George VI.

A week later we went on holiday for the first time ever, to Jaywick Sands, Clacton. The weather was great and we children spent all our time on the sands and in the sea. One day brother John and I were playing beside the breakwater, where one of the main posts entered the sand. We were in two feet of water and, as I stepped forward to the post, the sand suddenly gave way, and I slipped into a deep hole formed by the waves. When I tried to recover the sand would give way and I couldn’t pull myself out as the wood was covered with slimy weeds and I was drowning. Dad miraculously appeared and dragged me out, coughing up salt-water. I was badly scared, and since then I was always terrified of water, and never learned to swim.

My first experience of a professional match came on 26th October 1946 when father took me for my birthday to Selhurst Park to see Crystal Palace play. Dad saw them before the war when they had their great goal-scorer Peter Simpson, who still holds the record for the most goals in a season. Palace were in the Third Division South, and lost 2-1 to Port Vale, and dad said ‘They couldn’t beat the bloody blind school’. But they became my team from that day on and I’ve seen them rise to the Premiership, and have enjoyed great moments with them to the present day.

As winter approached, we had really bad fogs. They always seemed to happen around November and were a familiar event throughout my childhood, but these were really bad. It was incredibly difficult to find our way to school, with a visibility of just a few yards. We walked, holding walls of buildings like blind people, and crossing the roads was highly dangerous. When we blew our noses, our handkerchiefs would be black with the soot.

On Tuesday 25th December 1946 I was presented with one of dad’s very rare presents – a most wonderful fort that he had secretly made for me. It had castle battlements, a tower, and ivy growing on the walls, a moat of mirrored glass for water and a drawbridge and portcullis. I was thrilled, but disappointed that I had no soldiers to play with it. But luckily, a friend down the road got a box of Scottish soldiers in kilts, how they were dressed at the Battle of Waterloo. We would get together and have wonderful battles. The fort and soldiers were from completely different historical times, but it mattered not to us.

Twenty-two years later, I would scrape together enough money to buy the fortified and moated manor house Gedding Hall in Suffolk, where the oldest parts date from 1480, and which uncannily resembled that fort. And one of my hobbies became collecting military artefacts, including models of Scottish soldiers, probably a subconscious reaction to what I hadn’t had as a child.

The new year of 1947 began with the temperature falling to -16F, and snow fell throughout the first few weeks. For us kids, it was exciting, with everyone in the street making snowmen and having snowball fights. But it spelt disaster for the family, with dad out of work for weeks. It was also terribly cold in the house – the only heating coming from the stove in the kitchen. Our bedrooms were like refrigerators, and we kept warm by using every coat in the house on top of the thin blankets on our beds.

There wasn’t enough food to go round, and mum told us years later that they would keep us in bed in the mornings, telling us that it wasn’t time to get up, as there was no food in the house, until they would borrow from neighbours.

The freeze continued into the middle of March and followed by enormous flooding in the Fens, and other areas, and thousands of cattle and two million sheep died.

The weather improved and I started doing a milk-round in Penge and parts of Beckenham, and would earn six shillings a week, and had to give mum more than half of it. The milkman would sometimes take me fishing in the old Crystal Palace grounds, which were used during the war as an ammunition dump, and was fenced off with barbed wire. He showed me the way in through an old bent turnstile, and once in, we would fish the old breeding pond next to the large boating lake.

On Tuesday 8th April 1947, my youngest brother David Raymond was born with yellow jaundice and was admitted to hospital.

June was a glorious month, and I became fanatical about cricket, idolizing Dennis Compton and Bill Edrich of Middlesex in their greatest year. This led me to play 6 years of charity cricket later, together with all the cricket greats.

A month later I passed my scholarship examinations at Oakfield School, together with David Eastwood, and we were accepted into Beckenham and Penge Grammar School.

On Friday 15th August 1947, my baby brother David Raymond, just 4 months old, died of Yellow Jaundice and Pneumonia in the hospital. I was very cut up about it, and went to the market and bought a bunch of violets. Back at the house, his coffin was being brought out and had flowers on it. I put my flowers on it too, and mum in her grief threw them into the street. I was profoundly upset and the rejection stayed with me for years. He was buried at Elmers End Cemetry, Beckenham, in an unmarked grave, and we were not allowed to attend.

In early September I started at Beckenham and Penge Grammar School and quickly made many friends. Born and bred in one of the poorest parts of south-east London, what should have been an encouraging start in life quickly became a trauma. I had to wear a school uniform, which didn’t please dad, owing to the tightness of money.

At school the contrast between my background and other pupils was vast. Almost everyone came from upper and middle-class backgrounds, and lived in expensive homes, while I was definitely on the wrong side of the tracks. When I spoke normally in my ‘working-class’ accent, I would be made fun of at school. But if I tried talking better I was accused of being a ‘Snob’ by my friends and family. Father would regularly tell me that I was ‘Working Class – and not to even think of trying to become anything else’. Apart from that most of us pupils hated playing rugby instead of the football we loved.

During the spring term, hockey was played at school, and I found it almost impossible to play, owing to the fact that I was left-handed in all sports using a bat and ball, and hockey was only played right-handed.

We had to run the mile at school in under 7mins 30secs before the end of term, and I managed it in 6mins 33secs, at the age of 11, and felt very proud of my performance, and a year later I ran it in 6min 8secs.

We were told that there would be swimming classes after the Easter holidays, and I was terrified. I pleaded with my parents, and eventually complained of bad pains in my shoulders and back, and our family doctor diagnosed rheumatism, and I was excused from swimming for the rest of my schooldays.

In June 1948 uncle Jack sold his cooper business in New Cross and bought a modern 3 bedroom, semi-detached house at 23 Garden Road, Anerley, with a long garden, and everyone from gran’s flat moved there.

I continued having rows with dad about my schooling, and later that month I returned to live with my grandma again – this time in her new home, where I had the luxury of electricity, hot running water, a bathroom and toilet, and a television set with a tiny 6-inch screen – the first I’d ever seen. They bought a fitting filled with water that magnified the screen a little. On that grandma and I followed the cricket season. They also had a telephone in the house – another first for me.

Gran then enrolled me in piano lessons, and I also joined the choir at Holy Trinity Church, in Franklin Road. There we earned small sums of money for singing in the choir, and at weddings and funerals.

I was given 2 shillings and 6 pence by grandma each week for school dinners (twelve new pence today), and like most of the boys, I spent it on sweets and comics like the Rover and Wizard. My favourite hero was Wilson, the mysterious athlete who lived wild on the Yorkshire Moors and broke just about every ‘world record’ at athletics. Since then I’ve assembled a collection of Wizard comics featuring him – and his character still fascinates me.

Back at school in September 1948, my progress was generally good, apart from languages, and I did well in mathematics, history, art and music, and enjoyed my piano lessons after school and practised hard.

On Wednesday 3rd November 1948, I was issued with my last Identity Card, while living with Gran Jeffery.

A month later Gran Jeffery took me to the Royal College of Music, behind the Royal Albert Hall in London, where I passed my Primary examination on piano, and a few months later she took me again and I passed the Preliminary examination.

Returning to school in September 1949, I was envious of the richer boys that had great bicycles that they rode to school on, and I set my heart on a 3-speed Hercules, with drop handlebars, priced at £18. The only way to get it was to earn the money myself. So over the next 12 months, I continued with a morning milk round, a later paper round, and a bread round in the evenings, and after giving mum half my earnings, I ended up buying my bicycle.

On Monday 24th October 1949 I celebrated my 13th birthday, & as a present gran Jeffery took me to see Max Wall in ‘The White Horse Inn On Ice’ in London. He did a wonderful routine, and I became an instant fan of this great English Music Hall comedian.